Come on, we all know the feeling. You see Stone Cold setting up for the Stunner, or The Rock throwing the People’s Elbow, and something just clicks. These aren’t just moves — they’re the DNA of professional wrestling, passed down and evolved over decades. Some of them changed the business forever. Others just looked cool enough that everyone wanted to steal them.

That’s the thing about finishing moves in wrestling — they tell you everything about the era, the wrestler, and what the audience wanted to see. The Attitude Era gave us quick, explosive finishers like the Stunner and the RKO because fans wanted instant gratification. The technical wrestling boom brought submission specialists who could make grown men tap. And the high-flying revolution? Brother, that changed everything.

Here’s the reality: not all famous moves are created equal. Some became iconic because of the wrestlers who used them. Others were genuinely innovative and influenced an entire generation. And yeah, some just got lucky with timing and booking. We’re not just listing them — we’re telling you why they mattered, who did them best, and which ones are overrated.

🎯 What You’ll Find in This Guide

35+ moves across every era — ranked, rated, and explained

The Most Famous Wrestling Moves of All Time – And Why They Actually Matter

Stone Cold Steve Austin’s Stone Cold Stunner

Look, the Stunner wasn’t the most technical move you’ll ever see. It’s a simple three-quarter facelock dropped to a seated position, driving the opponent’s jaw into your shoulder. But what made Austin’s version special was the timing and the psychology behind it. When Austin hit that Stunner, it felt like a middle finger to authority — because that’s exactly what it was.

The move itself originated in Japanese wrestling, but Austin made it his own during the Attitude Era, when rebellion sold tickets. The real genius? Getting guys like The Rock and even WWE owner Vince McMahon to sell it like they’d been shot. That overselling became part of the spectacle.

What do you expect when you combine a simple move with perfect ring psychology? You get one of the most replicated finishers in wrestling history. Kids were hitting Stunners on each other for years after Austin’s prime. That’s cultural impact — and precisely why understanding a wrestler’s gimmick matters for appreciating what Austin built around it.

Shawn Michaels’ Sweet Chin Music

Now this is where showmanship meets precision. The Sweet Chin Music — just a superkick, really — became legendary because of what Michaels did before hitting it. That foot stomp in the corner, tuning up the band, building the anticipation. The move itself is a high-side thrust kick (technically called a Crescent Kick), but Michaels turned it into theater.

The thing that separates Sweet Chin Music from every other superkick? Placement and timing. When Michaels caught someone mid-air with that kick, it had to be perfect. One inch off and it looks terrible. Get it right, and it’s still one of the most beautiful finishers in wrestling history.

These days, everyone throws superkicks. The Young Bucks have cheapened it with their “Superkick Party” routine — and that’s part of their gimmick. But it’s made the move less special. Michaels used it sparingly, made it count. That’s the difference between a finisher and just another move.

The Rock’s People’s Elbow and Rock Bottom

The People’s Elbow is ridiculous. It’s literally just an elbow drop with extra steps: run the ropes, throw the elbow pad, drop the elbow. Technically, it should be the weakest finisher ever conceived.

But that’s not how wrestling works. The Rock turned a basic elbow drop into the most electrifying move in sports entertainment through pure charisma and showmanship. Same with the Rock Bottom — it’s a variation of the Uranage slam, nothing groundbreaking. But when The Rock hit it, it felt devastating because of how he sold his own offense.

Here’s what made both moves work: The Rock understood that wrestling is about connection with the audience. The People’s Elbow gave fans time to react, to chant, to be part of the moment. The Rock Bottom was quick and explosive when he needed the pop. He knew which tool to use when. That’s ring psychology at its finest.

Bret Hart’s Sharpshooter

If we’re talking about technically sound submission moves, the Sharpshooter sits at the top. Invented by Japanese legend Riki Choshu, but Bret “The Hitman” Hart made it famous through pure technical excellence — as documented in the WWE Hart and Soul documentary. The setup involves stepping over the opponent’s legs, turning them over, and sitting back to apply pressure on the lower back and legs.

What made Hart’s version special was the storytelling. He’d work the legs throughout the match, then lock in the Sharpshooter as the inevitable conclusion. That’s how you build a submission finisher — you tell the audience exactly what’s coming, and when it happens, it feels earned. That’s booking working hand in hand with in-ring craft.

The Montreal Screwjob made this move even more famous, and it has its own complicated legacy. But purely from a technical standpoint, the Sharpshooter is still taught in wrestling schools worldwide because it’s effective, safe, and looks painful. That’s the gold standard for a submission finisher.

Triple H’s Pedigree

The Pedigree is a double underhook facebuster that either looks devastating or downright sloppy, depending on who’s taking it. Triple H hooks both arms behind the opponent’s back and drives them face-first into the mat. When it’s done right — when guys like The Rock or Shawn Michaels took it — it looked career-ending.

That’s the thing about the Pedigree: it requires more cooperation from your opponent than most finishers. The person taking it has to position themselves perfectly, or it looks like garbage. But Triple H built his entire career around this move, using it to win 14 world championships. Smart booking and consistent use made it credible, even if it was never the most innovative finisher.

The move came from the independent scene — guys like Road Warrior Hawk used variations in the ’80s. But Triple H made it his signature during the Attitude Era and never looked back. That’s a masterclass in ownership: taking something that existed and making it so synonymous with your name that no one remembers who did it first.

Undertaker’s Tombstone Piledriver and Chokeslam

Here’s where we need to talk about banned moves and legacy protection. The Tombstone Piledriver — where you turn the opponent upside down and drop to your knees, driving their head toward the mat — has been functionally banned in WWE for years. Only The Undertaker and Kane could use it, and now that they’re retired, you barely see it.

Why? Because piledrivers are dangerous. Owen Hart’s botched piledriver nearly paralyzed Steve Austin in 1997. The Tombstone is safer than the traditional piledriver if executed correctly, but WWE doesn’t trust most wrestlers to do it right. So it became Undertaker’s move by default — part legacy protection, part genuine safety policy.

The Chokeslam, on the other hand, is still widely used because it’s relatively safe and looks spectacular. Undertaker didn’t invent it, but his version — lifting opponents high and slamming them with authority — became the template everyone copied. Both moves worked because of his character. A supernatural wrestler needed supernatural-looking finishers. The psychology made perfect sense.

Rey Mysterio’s 619

The 619 is one of those moves that shouldn’t work as well as it does. Mysterio delivers a spinning kick through the ropes to an opponent draped over the second rope, then follows up with a springboard move. The setup is contrived, the execution requires perfect positioning, and realistically, opponents should see it coming every time.

But it works because it’s unique, it looks spectacular, and Mysterio’s athleticism sells it completely. Named after San Diego’s area code, the 619 became Mysterio’s signature during his WWE run and helped define the cruiserweight style in American wrestling.

What do you expect from a high-flyer who revolutionized what smaller wrestlers could do in WWE? You get innovation born from necessity. Mysterio couldn’t powerbomb guys, so he built offense around his agility. The 619 is the perfect example of playing to your strengths — and understanding your role as a babyface who the crowd desperately wants to see win.

Goldberg’s Spear and Jackhammer

Goldberg’s entire offense was built around intensity and power, and his two finishers embodied that perfectly. The Spear — a running shoulder tackle — and the Jackhammer — a delayed vertical suplex dropped into a slam — were both about overwhelming opponents with raw strength.

The Spear itself isn’t innovative. Edge used it. Roman Reigns uses it. Rhino’s Gore was arguably more impactful. But Goldberg’s Spear in WCW came attached to an undefeated streak, making it feel genuinely unstoppable. Same with the Jackhammer — it’s just a stalling suplex, but when you’re 173-0, every move looks devastating.

That’s the lesson here: booking matters more than the move itself. Goldberg’s finishers worked because WCW protected him. The second his streak ended, the moves lost their mystique. It’s all about presentation — which is exactly the debate we explore in our look at AEW vs. WWE’s approach to building stars.

Randy Orton’s RKO

The RKO is a jumping cutter — a three-quarter facelock where Orton leaps and drives the opponent’s face into the mat. It’s not original; Diamond Dallas Page used the Diamond Cutter in WCW, which was essentially the same move. But Orton made it his own through timing and variation.

What makes the RKO special is its versatility. Orton can hit it from anywhere — mid-air off a springboard, as a counter to someone diving at him, or out of nowhere during a sequence. That unpredictability is what keeps it over with fans. The “RKO outta nowhere” became a meme for a reason.

Standard RKO: The classic version — Orton grabs his opponent’s head in a three-quarter facelock and swiftly drops to the mat, driving their face into the canvas. Executable from standing or as a direct counter, this is the foundation for everything else.

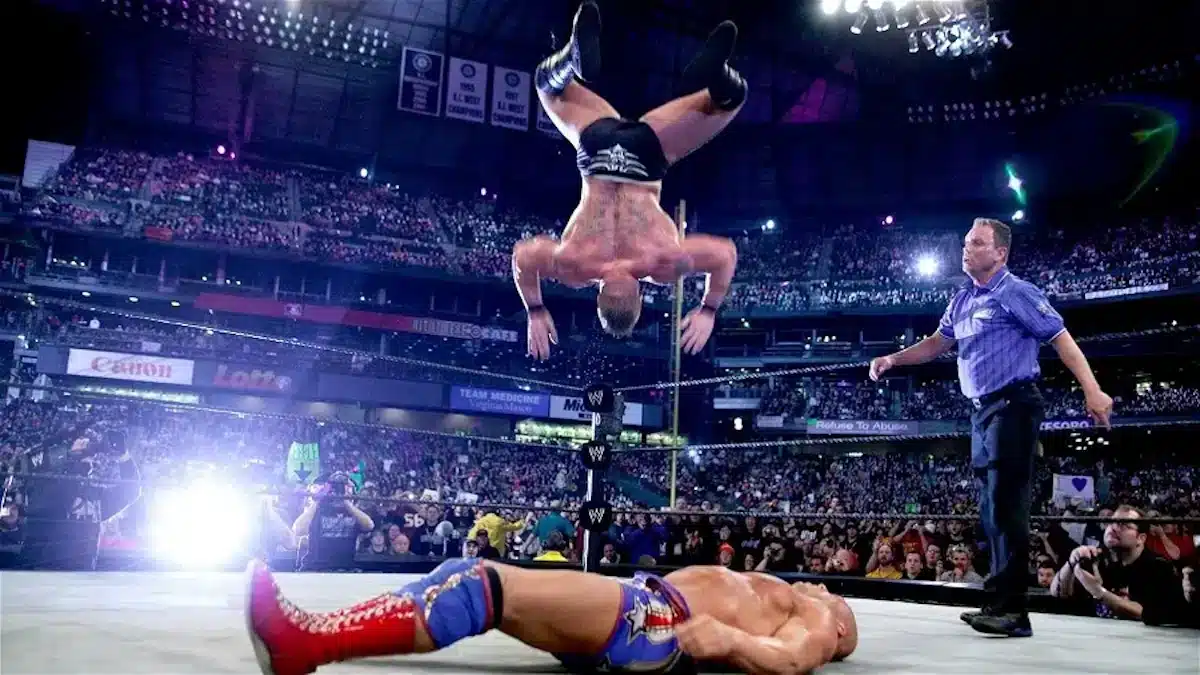

Springboard RKO: Orton intercepts an opponent leaping from the ropes mid-flight. The defining example came at WrestleMania 31 when he countered Seth Rollins’ Curb Stomp attempt with a mid-air RKO — one of the most memorable spots of the decade.

Elevated RKO: Delivered from the top rope or a ladder, this high-risk variation adds dramatic impact and often closes out major matches on the biggest stages.

Running RKO: Orton sprints toward his opponent before executing, adding momentum and force — particularly effective against charging opponents who walk right into it.

Pop-Up RKO: Orton lifts the opponent into the air before catching them on the way down with the RKO, emphasizing strength and timing simultaneously. These variations demonstrate why the RKO ages so well — it doesn’t require peak athleticism; it requires awareness and craft.

John Cena’s Attitude Adjustment

The Attitude Adjustment — formerly called the F-U as a shot at Brock Lesnar’s F-5 — is a fireman’s carry takeover where Cena flips the opponent off his shoulders and slams them to the mat. It’s not technically complex, but it showcases Cena’s legitimate strength and fits his character as the never-give-up babyface who overpowers opponents through sheer will.

Here’s the reality: Cena used this move to win 16 world championships. That’s the only stat that ultimately matters. Reliable, safe, and well-branded — it did its job for nearly two decades.

The problem? Cena kicked out of so many finishers during his run that his own finisher got devalued by comparison. How many times did guys kick out of the AA? Too many. That’s the danger of 50/50 booking — even your top star’s finisher loses its authority when it can’t reliably end a match. It’s a cautionary tale about what happens when WWE loses the thread on protecting its stars.

Breathtaking Topé Suicida

This term, often used in Spanish as “suicida,” precedes any maneuver executed from inside the wrestling ring to its exterior. The most common example is the suicide dive — known in Spanish as “topé suicida,” translating to “suicide headbutt.” When a wrestler performs a somersault after springing through or over the top rope to land back-first on their opponent, this is called a topé con giro (“spinning headbutt”). Outside Mexico, this move is sometimes inaccurately called “topé con hilo,” a mistranslation originating in Japan — “hilo” in Spanish simply means “thread.”

These moves represent an entire tradition of lucha libre innovation that reshaped American wrestling’s relationship with aerial offense. Understanding where these techniques come from is part of appreciating the business’s deep roots — roots that stretch back to the catch-as-catch-can tradition that predates WWE by a century.

High-Flying Finishers: Evolution and Impact

The Swanton Bomb, Shooting Star Press, and Frog Splash all came from different wrestling traditions but converged in American wrestling during the late ’90s and early 2000s, raising the bar for what audiences expected from aerial performers. These are the moves that changed what wrestling looked like.

Jeff Hardy’s Swanton Bomb

The Swanton Bomb is a corkscrew senton — Hardy climbs to the top rope, executes a complete backflip rotation, and lands back-first on the opponent. It looks impressive, it’s high-risk, and it perfectly captures Hardy’s daredevil character. What made his version iconic was where he’d hit it from. Normal top rope? Sure. Ladder? Absolutely. Steel cage? Why not. The move scaled with the stipulation, and Hardy’s willingness to put his body on the line made it credible. The downside: it destroyed his body over time. That’s the permanent trade-off of high-flying offense.

Shooting Star Press

The Shooting Star Press — a backflip off the top rope landing chest-first on the opponent — was pioneered by Jushin Thunder Liger in Japan in 1987. It requires incredible athleticism, precision timing, and complete trust that you won’t land on your opponent’s knees. Billy Kidman made it famous in WCW. Guys like Ricochet and Evan Bourne elevated it in WWE. The problem? It’s risky. Brock Lesnar nearly killed himself attempting one at WrestleMania 19, and WWE essentially stopped promoting the move after that unless a performer could prove they could execute it safely and consistently. That’s the evolution of wrestling right there.

Frog Splash

Eddie Guerrero’s Frog Splash became synonymous with his legacy, even though he didn’t invent it. The move involves jumping off the top rope with arms and legs spread wide, then bringing them in to land chest-first on the opponent. What made Eddie’s version special was the storytelling around it — he’d sometimes hesitate before hitting it, selling exhaustion or emotion, turning a simple top-rope move into a character moment. Rob Van Dam used a version he called the Five-Star Frog Splash, but Eddie made the original mean something beyond the athletic execution.

Submission Specialists: Technical Mastery

Submission moves require a different skill set than strikes or slams. You need to tell a story through limb targeting, sell the progression of pain, and make the audience believe someone might actually tap. For a deep statistical look at how submissions play out in a combat sports context, our breakdown of the most common submissions in MMA shows that many of these wrestling techniques have direct real-world counterparts.

Kurt Angle’s Ankle Lock

The Ankle Lock is exactly what it sounds like — grab the opponent’s foot and twist to hyperextend the ankle. Kurt Angle made this move famous during his Olympic wrestling career, and it fit perfectly with his amateur background. He’d grab the ankle and just torque it, sometimes adding a grapevine with his legs for extra pressure. Ken Shamrock used a similar move in WWE, but Angle perfected it. The ankle lock is still taught as a fundamental submission hold because it’s believable, relatively safe, and has built-in drama through rope breaks and counters. It works whether you’re a heel being vicious or a babyface using it as a desperate last resort.

Ric Flair’s Figure Four Leglock

The Figure Four Leglock predates Ric Flair — Buddy Rogers used it first, then Riki Choshu popularized it internationally. But “The Nature Boy” made it iconic through decades of consistent use and showmanship. The move involves crossing the opponent’s legs in a figure-four shape and sitting back to apply pressure on the knee and ankle. Flair did this for 40 years, which is a remarkable achievement in itself. Charlotte Flair evolved it with the Figure Eight — bridging backward to add elevation and more pressure. That’s how you honor a legacy while building your own.

Chris Benoit’s Crippler Crossface

We need to address this one carefully. The Crippler Crossface — a crossface chickenwing where you trap the opponent’s arm and wrench their neck backward — was one of the most effective submission finishers in WWE history. The move itself is technically sound. Mercedes Moné (formerly Sasha Banks) adapted it into the Bank Statement. Daniel Bryan used variations. The technique is valid and legitimate. Benoit’s legacy is complicated by his actions in 2007, and WWE has essentially erased him from history. The Crossface as a move type persists in various forms because it targets the neck and arm simultaneously, appears genuinely painful, and has multiple pressure points. That’s why it endures, now entirely separated from the man who made it famous.

Tag Team Finishers: Coordinated Chaos

Tag team wrestling requires finishers that showcase teamwork and timing. The best tag finishers look impossible to execute without perfect coordination — and they require a level of trust between partners that takes years to develop.

Dudley Boyz’s 3D (Dudley Death Drop)

The 3D combines a flapjack from Bubba Ray with a cutter from D-Von — one wrestler lifts the opponent while the other catches them mid-air with a jumping cutter. When executed correctly, it looks devastating. What made the Dudley Boyz’s version special was their consistency: they could hit the 3D on anyone from cruiserweights to super heavyweights, and they’d often put opponents through tables in the process. The move requires absolute trust between partners and perfect timing. One second off and it fails completely — which is why you don’t see it copied as often as single-performer finishers.

Legion of Doom’s Doomsday Device

The Doomsday Device is old-school power: Animal lifts the opponent onto his shoulders while Hawk jumps off the top rope with a clothesline. Simple concept, massive impact. What do you expect from the Road Warriors? They invented power tag team wrestling. The Doomsday Device was their exclamation point — no fancy setup, no complicated choreography, just raw intimidation. Physics plus psychology. Modern variations exist, but the original is still the template.

Women’s Division: Breaking New Ground

Women’s wrestling finishers have evolved dramatically over the past decade. Early women’s finishers were often just scaled-down versions of men’s moves. Modern women’s wrestlers create finishers that showcase their unique styles and athleticism — a shift that reflects broader changes in how both WWE and AEW book their women’s divisions, as explored in our AEW vs. WWE comparison.

Charlotte Flair’s Figure Eight

Charlotte took her father’s Figure Four Leglock and evolved it by bridging backward, adding elevation and significantly more pressure to the opponent’s legs. The Figure Eight requires core strength and flexibility that most wrestlers simply don’t have. It carries the weight of the Flair name while establishing something Charlotte genuinely owns — respect the past, build your own future. That’s how wrestling legacies are supposed to work.

Mercedes Moné’s (Sasha Banks) Bank Statement

The Bank Statement is Mercedes’s variation of the Crossface — she traps the opponent’s arms and applies a crossface, adding body scissors for additional pressure. What made it work in WWE was her willingness to target specific body parts throughout matches, then lock in the Bank Statement as the logical conclusion. That’s ring psychology 101, and she executes it perfectly. The challenge with submission finishers for smaller wrestlers is credibility — Mercedes solved this through consistent execution and smart match structure.

Becky Lynch’s Dis-arm-her

The Dis-arm-her is a modified armbar where Becky traps the opponent’s arm between her legs and hyperextends the shoulder — a legitimate MMA technique adapted for professional wrestling. The “The Man” character required a finisher that looked aggressive and painful. The Dis-arm-her delivers both. Within three years of making it her signature, Becky became the face of WWE’s women’s division. Your finisher really does tell the audience who you are as a performer.

Modern Era: Innovation Continues

Today’s wrestling finishers balance athleticism, safety, and spectacle. The three moves below define the current generation — and each one tells a story about what modern wrestling values.

Seth Rollins’ Curb Stomp (The Stomp)

The Curb Stomp is precisely what it sounds like — Rollins stomps on the back of an opponent’s head while they’re on their hands and knees. It was banned for years due to its violent appearance, then brought back with slight modifications. This move works because of its simplicity and suddenness. Rollins can hit it out of nowhere, which creates unpredictability without requiring a complex setup. The controversy around the move’s name actually helped it — WWE tried to rebrand it as “The Stomp,” but fans knew exactly what it was. Sometimes controversy is the best promotional tool available.

Roman Reigns’ Spear

Roman’s Spear is the culmination of decades of wrestlers using the move. He launches himself at opponents like a linebacker, and the presentation — the loading up, the building of anticipation — makes it feel distinct from every other Spear in wrestling. Goldberg, Edge, Rhino, and countless others have used it. What makes Roman’s version work is veteran ring psychology: he makes the audience anticipate it, then delivers. The Spear ages well because it doesn’t require peak athleticism — it requires timing, presence, and the right character to sell it.

AJ Styles’ Styles Clash

The Styles Clash is a unique facebuster where AJ hooks the opponent’s arms behind their back, lifts them up, and falls forward to drive their face and chest into the mat. AJ reportedly created this move accidentally while playing on a trampoline with his brother — either the best or worst origin story in wrestling history, depending on your perspective. The move has been controversial due to instances where wrestlers didn’t tuck their chins properly and suffered neck injuries. But what makes it work is that it’s uniquely AJ’s. In an era where everyone steals everyone’s moves, genuine distinctiveness matters. That’s branding, which is just the gimmick taken to its logical conclusion.

The Banned List: Safety Versus Spectacle

Professional wrestling’s relationship with dangerous moves is complicated. Some got banned because they were legitimately unsafe. Others were banned due to liability concerns or changing standards. Understanding the difference is key to appreciating how the business has evolved.

The piledriver became functionally banned after Owen Hart’s botched version nearly paralyzed Steve Austin in 1997 — only protected veterans like The Undertaker could use variations after that. Chair shots to the head disappeared in 2010 when WWE formally acknowledged concussion research. The Curb Stomp was temporarily banned due to violent optics, not actual safety concerns. Buckle Bombs got restricted after Sting’s career-ending injury in 2015.

The WWE heart punch ban isn’t just corporate caution — it’s wrestling evolving past its carnival roots. This finishing move was sold as literally stopping your opponent’s heart, and in an era of shareholder meetings and mainstream media scrutiny, that psychology doesn’t fly. AEW has gone through similar learning curves, banning unprotected head shots and several high-risk moves as the promotion matured. Tony Khan is learning the same lessons WWE learned the hard way.

🚫 Notable Banned or Restricted WWE Moves

What Makes a Move Truly Iconic?

After analyzing 35 of wrestling’s most famous moves, clear patterns emerge. The best finishers share these characteristics.

Simplicity — The Stone Cold Stunner, RKO, and Spear are all simple concepts executed with perfect timing. Complexity doesn’t equal effectiveness. The audience needs to follow what happened in real time.

Character alignment — The Undertaker’s supernatural finishers matched his character. Cena’s Attitude Adjustment reflected his never-give-up persona. When character and finisher are misaligned, the disconnect reads immediately.

Versatility — Moves that can be hit from multiple positions or in different contexts (like the RKO) stay over longer than one-trick finishers. Longevity requires adaptability.

Safety — Moves that injure people regularly don’t last. The piledriver is proof. The best finishers protect both wrestlers while looking devastating. This is a craft skill, not an afterthought.

Booking — Even the best move fails without proper protection. Goldberg’s Spear and Jackhammer worked because he was booked as unbeatable. When the booking changed, the moves meant less. The story around the move matters as much as the move itself.

Innovation — Moves that brought something genuinely new to wrestling (Mysterio’s 619, Styles’ Styles Clash) have longer legacies than moves that copy what came before. Being first matters. Being distinctive matters more.

The Future: Where Finishers Are Headed

Finishers are evolving in two directions simultaneously. One branch trends toward submission-based finishers that mirror MMA credibility — a logical development as the lines between combat sports continue to blur. The other trend toward high-flying spectacle that generates viral clips. Both have commercial logic.

Submission finishers are making a comeback because they tell longer stories and don’t require the kind of bumps that shorten careers. As wrestlers get smarter about protecting their bodies, expect more armbar variations and leglocks to headline major events. Tag team finishers are also due for a renaissance — both WWE and AEW have invested in their tag divisions, and the genre desperately needs a new Doomsday Device and 3D equivalent for this generation. The templates exist; someone just needs to execute them with modern athletes and the right promotional push.

Why This All Matters

Come on, we’re talking about choreographed moves in predetermined matches. Why does any of this matter?

Because finishers are how wrestling creates its defining moments. Stone Cold’s Stunner on Vince McMahon represented rebellion against authority. When Daniel Bryan made Batista tap at WrestleMania 30, it represented the underdog finally winning. When Becky Lynch made Charlotte tap with the Dis-arm-her, it signified the women’s revolution arriving at the top of the card.

The moves themselves are just movements. The context, the character work, the booking — that’s what makes them iconic. That’s also why shoots and works and kayfabe matter to understand — because the emotional reality that wrestling creates is built on a foundation of deliberate craft, not improvised chaos.

So the next time you see someone hit their finisher, remember: you’re watching decades of evolution, multiple wrestling traditions, and someone’s careful character work all compressed into three seconds. That’s pretty remarkable when you think about it.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the most famous wrestling move of all time?

The Stone Cold Stunner is widely considered the most culturally iconic wrestling move of all time, combining simplicity, perfect timing, and a character-defining context that resonated far beyond the wrestling audience. The RKO runs a close second thanks to its extreme versatility and the “RKO outta nowhere” meme that introduced it to an entirely new generation of fans.

What’s The Rock’s signature move?

The Rock’s signature moves are unmistakable: The People’s Elbow, The Samoan Drop, the Rock Bottom, and The People’s Eyebrow. The People’s Elbow is technically the weakest-looking finisher in history and simultaneously one of the most over moves ever — which tells you everything about how charisma functions in professional wrestling.

What is Hulk Hogan’s signature move?

Hulk Hogan’s finishing move is the iconic Leg Drop — sometimes called the Atomic Leg Drop. It involves dropping his leg across a fallen opponent’s chest or throat from a standing position. Simple, unimpressive technically, and over for decades purely through Hogan’s presentation and the era’s booking standards.

What are Booker T’s finishing moves?

The Scissors Kick and Book End became Booker T’s most recognizable finishing moves, particularly during his main event run as a five-time WCW Champion and later WWE World Heavyweight Champion. The Scissors Kick — a jumping heel kick to the back of a bent-over opponent’s neck — was his most visually distinctive finisher.

What is the difference between a finisher and a signature move?

A finisher is a wrestler’s most potent move, specifically protected by booking to end matches — when it’s hit cleanly, the match typically ends. A signature move is a recognizable move used regularly throughout matches, but doesn’t necessarily result in a pinfall or submission. The People’s Elbow is a finisher; The Rock’s eyebrow raise is a signature. Both are part of the same character package.

Why do some wrestling moves get banned?

Moves get banned for two distinct reasons: genuine safety concerns (piledrivers, chair shots to the head, buckle bombs) or presentation concerns (the Curb Stomp’s name, the heart punch’s implications). The former reflects wrestling’s evolution as a physically demanding performance art where performer safety increasingly outweighs spectacle. The latter reflects corporate wrestling’s sensitivity to mainstream perception and brand partnerships.

Which wrestling promotion — WWE or AEW — allows more dangerous moves?

AEW generally allows a wider range of high-risk moves than WWE, reflecting different philosophies about performer autonomy and product presentation. WWE has stricter policies driven by its corporate structure, insurance requirements, and concern for long-term performer availability. Both promotions have moved toward greater safety consciousness over time, though AEW still permits moves that would be restricted on WWE programming.

Related Reading

- Finishers Explained: What Makes a Signature Move Work

- Ring Psychology: Crafting Wrestling Stories

- Booking 101: Building Wrestling Storylines

- Defining the Heel in Pro Wrestling

- Who Is the Face in Pro Wrestling?

- What Is Kayfabe? A Fun Guide to Pro Wrestling’s Biggest Open Secret

- Inside the “Gimmick” of Pro Wrestling

- The Cradle: Wrestling’s Sneaky Pin Explained

- Most Common Submissions in MMA: The Complete Statistical Breakdown

- Before MMA: A Guide to Catch-As-Catch-Can Wrestling